JAMSU BRIDGe

Principal Use: Bridge

Project Site: Seoul, Korea

Design Period: 2023.08

Hose: Seoul Metropolitan Government

Project Site: Seoul, Korea

Design Period: 2023.08

Hose: Seoul Metropolitan Government

This is the next chapter in the varied history of Jamsu Bridge, a half-century-old bridge on the Han River in Seoul originally designed for military vehicles, but now, and for the foreseeable future, a haven for pedestrian and bicycle traffic linking Seoul's northern and southern halves.

It is an inquiry into how a bridge designed with an unusually low height, a raised arch for passing watercraft, and a military aesthetic might be repurposed for regular pedestrians in desperate need of leisure space in a rapidly growing metropolis. At the same time, it is an experiment that considers basic spatial relationships—(1) between people and their environment, and (2) between people themselves—and the profound benefits they can have on the mental health of busy city dwellers when such relationships are designed with intention.

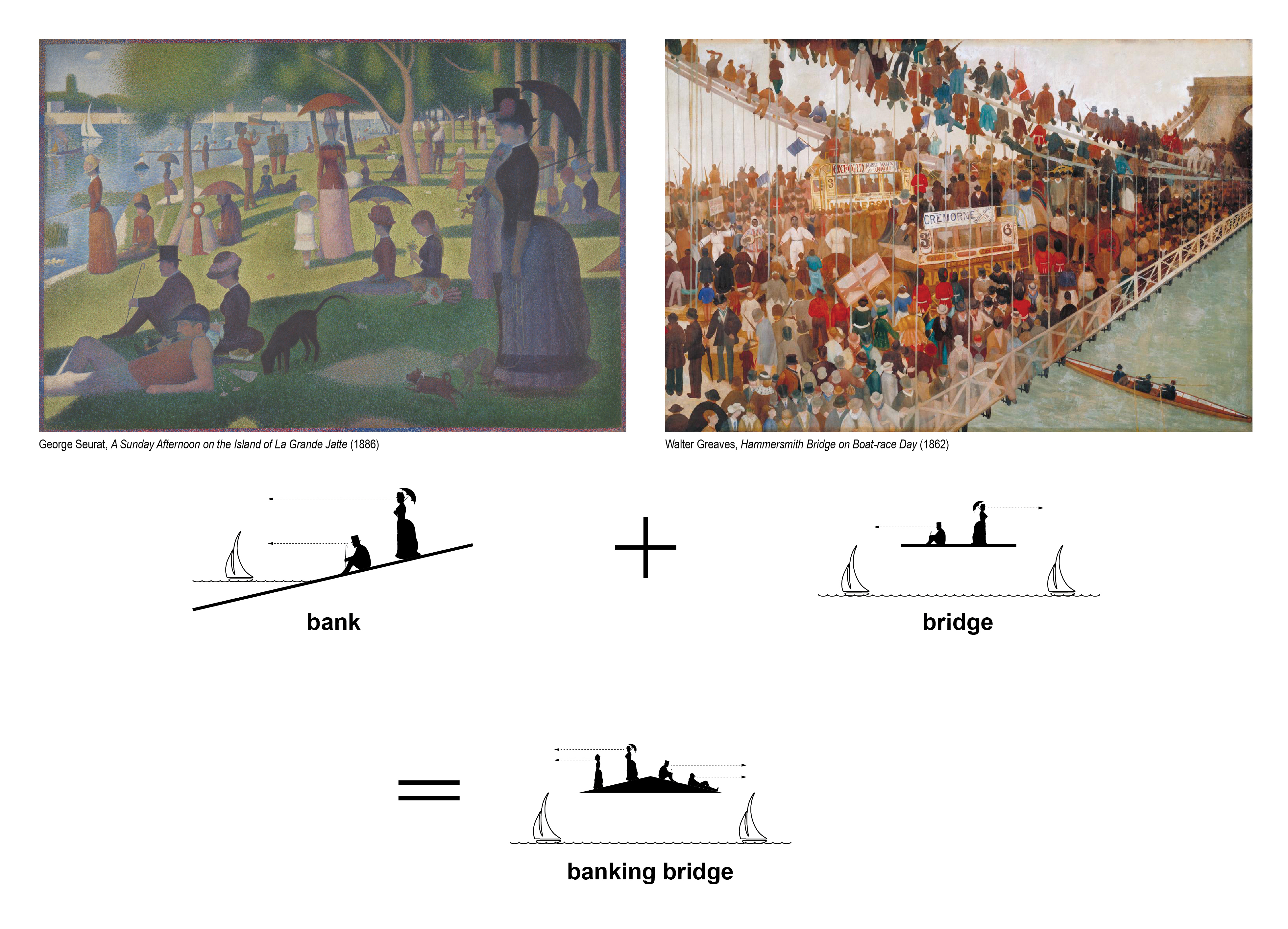

Two interesting phenomena can be observed at rivers and bridges. When people walking along the bank of a river stop to talk, they almost always face the river rather than each other. This is because of the natural slope of the bank but also because of the activity happening on the river itself, whether it is a boat, an animal, or simply the water’s surface. Similarly, on a bridge people are naturally inclined to cast their gaze upriver or downriver, and depending on the size of the bridge they may be able to look both ways from the same place without having to move. In each case, the pleasurable diversions of the river in combination with the peoples’ spatial orientation, both to the river and to each other, produce an atmosphere of informality. Conversation is relaxed, and subject matter more fluid. Silent pauses, which normally signal the death of conversation, become opportunities for further discussion.

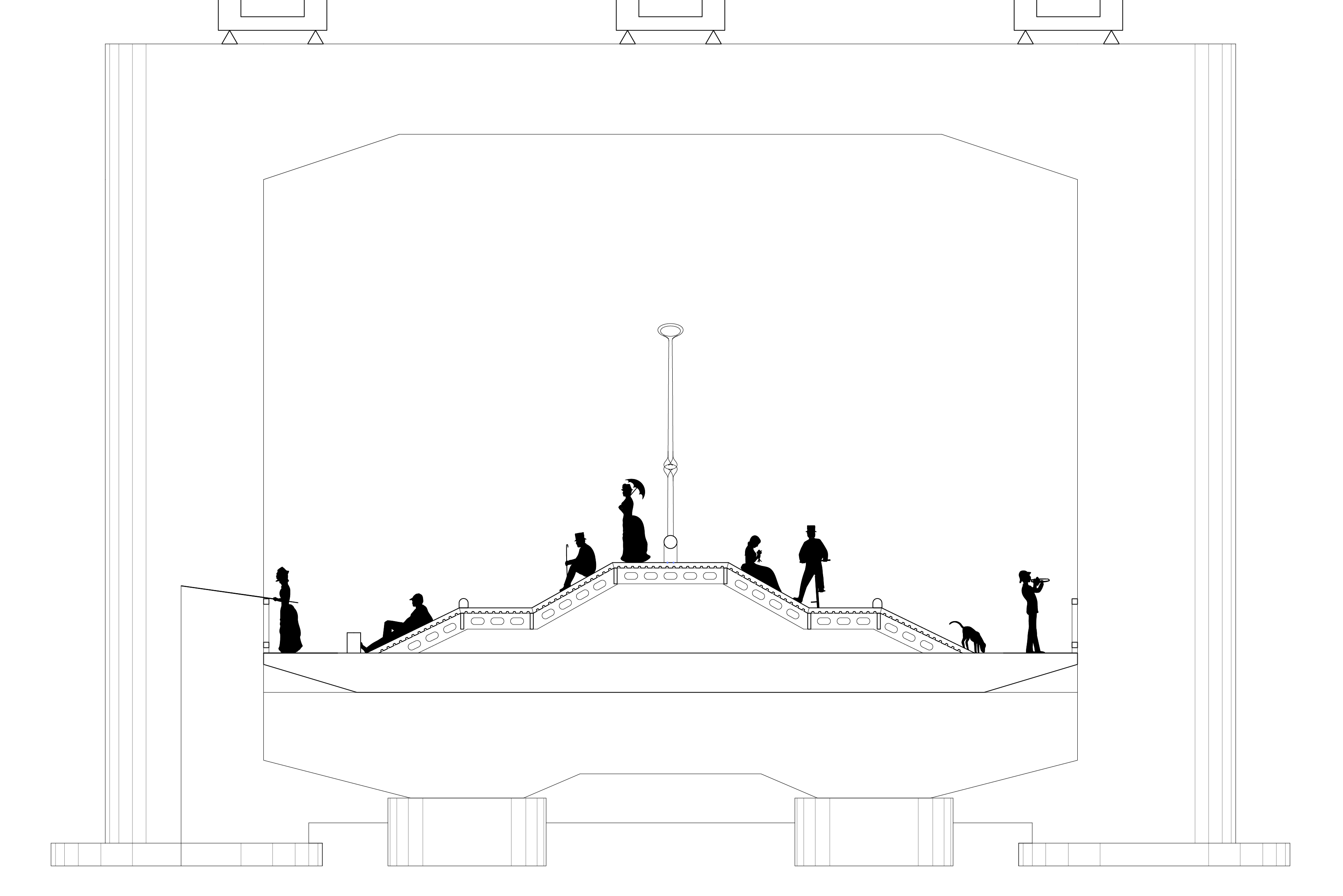

Through this proposal we are interested in reaping the psychological benefits of such social-spatial interactions by combining the “bank” and the “bridge.” Into the city’s existing design standards for pedestrian paths (green) and cycling paths (red) we propose a third surface separating the other two, and dedicated to no particular function other than to be used at one’s leisure. This yellow surface slopes gently in cross-section such that guards and handrails are not required, resulting in minimal obstruction of movement and views, and a comfortable sitting surface oriented toward the river. It acts as a buffer separating the green and red circulatory spaces from each other—a slow space in which people are free to pause and appreciate their surroundings.

By nature of their cross-sectional slope these yellow surfaces separate the green and red surfaces in the vertical direction as well, coming together to form a terraced cross-section that is highest in the middle and lowest at the sides. The raised surfaces are built up from the existing roadway, and their constructed forms are used repetitively in different arrangements throughout the bridge to minimize the cost of design and construction.

Feeding into this parallel formation of terraced pathways are all of the existing walking and cycling routes that line the north and south banks. Connections to these routes are made in places that allow for natural flow of movement while maintaining a safe separation of cyclists and pedestrians. More invasive integration of the urban fabric happens at a few key points—for example, the extension of an existing underground pedestrian crossing at the north approach.

With its new pedestrian-only designation and the freedoms from design constraints that come with this, Jamsu Bridge is uniquely positioned as a site for radical architectural experimentation. But the desire for novelty must be met with due consideration given to the social needs of the project. To borrow sociologist Ray Oldenburg’s term, we believe that a city’s “third places”—places other than home and work—when they are designed well, their benefits are hard to quantify, yet they are undeniably essential to the long-term prosperity of a city. Our proposal for functional, durable, and pleasurable shared space, converging at the middle point of Gangnam and Gangbuk, seeks to be one such “third place” in the lives of Seoul’s residents and a model for others to come.

It is an inquiry into how a bridge designed with an unusually low height, a raised arch for passing watercraft, and a military aesthetic might be repurposed for regular pedestrians in desperate need of leisure space in a rapidly growing metropolis. At the same time, it is an experiment that considers basic spatial relationships—(1) between people and their environment, and (2) between people themselves—and the profound benefits they can have on the mental health of busy city dwellers when such relationships are designed with intention.

Two interesting phenomena can be observed at rivers and bridges. When people walking along the bank of a river stop to talk, they almost always face the river rather than each other. This is because of the natural slope of the bank but also because of the activity happening on the river itself, whether it is a boat, an animal, or simply the water’s surface. Similarly, on a bridge people are naturally inclined to cast their gaze upriver or downriver, and depending on the size of the bridge they may be able to look both ways from the same place without having to move. In each case, the pleasurable diversions of the river in combination with the peoples’ spatial orientation, both to the river and to each other, produce an atmosphere of informality. Conversation is relaxed, and subject matter more fluid. Silent pauses, which normally signal the death of conversation, become opportunities for further discussion.

Through this proposal we are interested in reaping the psychological benefits of such social-spatial interactions by combining the “bank” and the “bridge.” Into the city’s existing design standards for pedestrian paths (green) and cycling paths (red) we propose a third surface separating the other two, and dedicated to no particular function other than to be used at one’s leisure. This yellow surface slopes gently in cross-section such that guards and handrails are not required, resulting in minimal obstruction of movement and views, and a comfortable sitting surface oriented toward the river. It acts as a buffer separating the green and red circulatory spaces from each other—a slow space in which people are free to pause and appreciate their surroundings.

By nature of their cross-sectional slope these yellow surfaces separate the green and red surfaces in the vertical direction as well, coming together to form a terraced cross-section that is highest in the middle and lowest at the sides. The raised surfaces are built up from the existing roadway, and their constructed forms are used repetitively in different arrangements throughout the bridge to minimize the cost of design and construction.

Feeding into this parallel formation of terraced pathways are all of the existing walking and cycling routes that line the north and south banks. Connections to these routes are made in places that allow for natural flow of movement while maintaining a safe separation of cyclists and pedestrians. More invasive integration of the urban fabric happens at a few key points—for example, the extension of an existing underground pedestrian crossing at the north approach.

With its new pedestrian-only designation and the freedoms from design constraints that come with this, Jamsu Bridge is uniquely positioned as a site for radical architectural experimentation. But the desire for novelty must be met with due consideration given to the social needs of the project. To borrow sociologist Ray Oldenburg’s term, we believe that a city’s “third places”—places other than home and work—when they are designed well, their benefits are hard to quantify, yet they are undeniably essential to the long-term prosperity of a city. Our proposal for functional, durable, and pleasurable shared space, converging at the middle point of Gangnam and Gangbuk, seeks to be one such “third place” in the lives of Seoul’s residents and a model for others to come.