C.S.O.Q.B.

Principal Use: Exhibition

Project Site: New York

Exhibition: International Architecture Biennale Rotterdam: “The Communal City, The Learning City”

Collaborator: Bingyu Guan

Project Site: New York

Exhibition: International Architecture Biennale Rotterdam: “The Communal City, The Learning City”

Collaborator: Bingyu Guan

Combined Sewer Overflow of Queens and Bronx

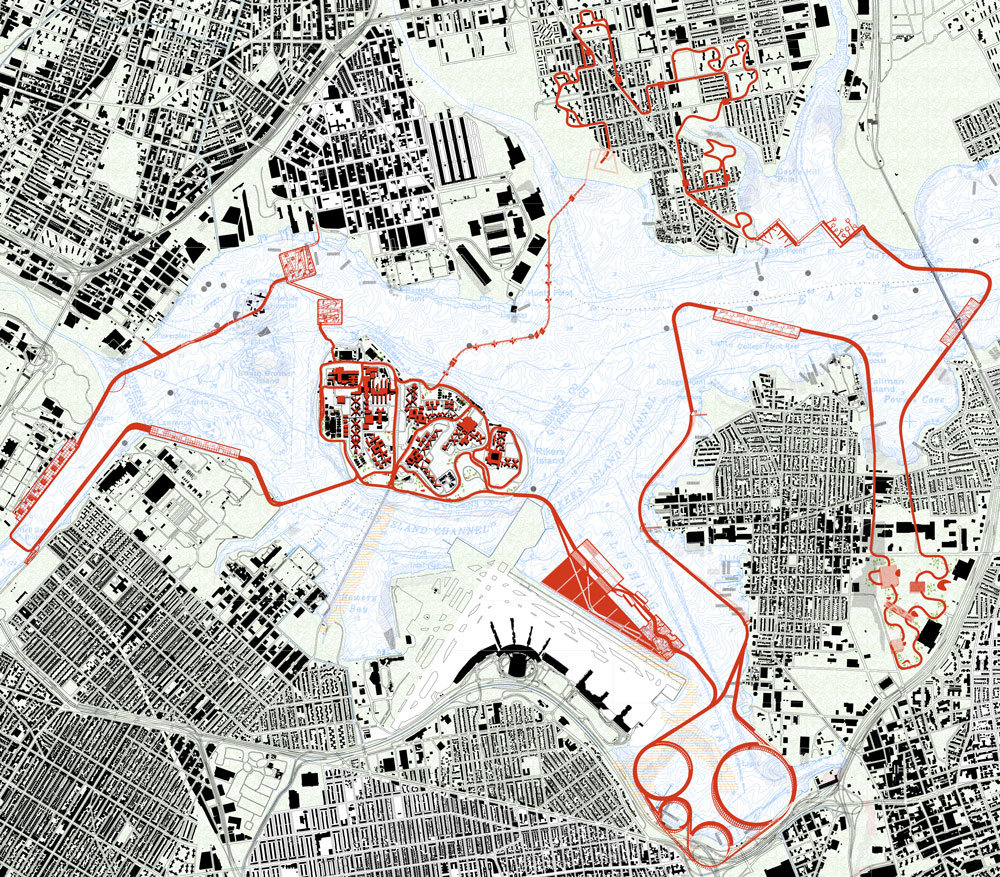

It would not be untrue to say that the East River wasn’t the dirtiest river in New York City, but the distinction is of little account. Like the Hudson, its slightly filthier counterpart, the East River has served New York throughout its history as a receptacle for all kinds of pollution. Today, it is fronted by many of the city’s heavy-industrial brownfield sites, and is the dumping ground for 139 combined sewer overflows, or C.S.O.’s, which provide a regular supply of stormwater runoff—5 billion gallons annually—containing raw human waste, industrial waste, and toxic materials, making the river a perfect home for dangerous bacteria such as enterococci.

The river is also home to Rikers Island, which has served as a geographically convenient island-jail for almost a century. But now, with its 400 acres of relatively undeveloped, uncontaminated land, public opinion has reached a consensus that the island would be better zoned as recreational open space for the ever-densifying Bronx and Queens neighborhoods nearby as well as prime real estate to be sold to the city’s growing research and educational institutions.

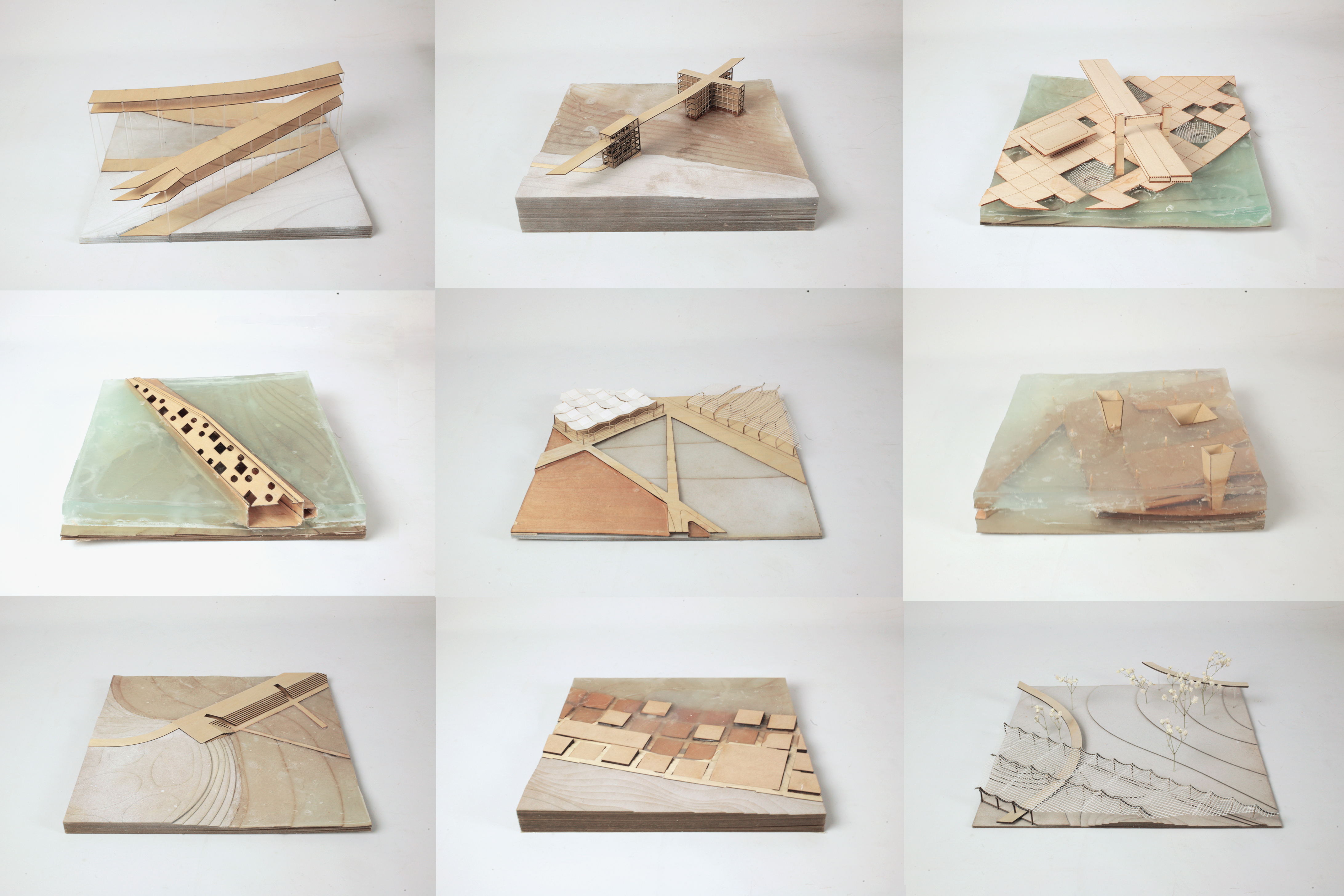

Our response to the Biennale’s theme “The Communal City, The Learning City” is a radical vision for the five-mile stretch of river between Randall’s Island to the west and Whitestone Bridge to the east, wherein the city begins a slow process of expansion into the river through new construction methods applied at the convergence of current social and economic forces:

1) It anticipates a growing need for slow infrastructure—roads and facilities aimed at creating safe outdoor recreational space specifically for pedestrians and cyclists—while providing a solution to the great transportational divide separating these two boroughs.

2) It sets in motion a massive undertaking to treat the last major source of pollution plaguing the river, with sewer overflow from all 139 C.S.O.’s being redirected to water treatment pipelines before flowing into the river.

3) It recovers a valuable piece of land much needed for future populations as the outer boroughs continue to densify, and at the same time affords opportunities for architectural innovation in the area of correctional facilities.

It is, we believe, a logical next step in the city’s development, and may be the key to correcting New York’s relationship with this formerly mistreated body of water.

It would not be untrue to say that the East River wasn’t the dirtiest river in New York City, but the distinction is of little account. Like the Hudson, its slightly filthier counterpart, the East River has served New York throughout its history as a receptacle for all kinds of pollution. Today, it is fronted by many of the city’s heavy-industrial brownfield sites, and is the dumping ground for 139 combined sewer overflows, or C.S.O.’s, which provide a regular supply of stormwater runoff—5 billion gallons annually—containing raw human waste, industrial waste, and toxic materials, making the river a perfect home for dangerous bacteria such as enterococci.

The river is also home to Rikers Island, which has served as a geographically convenient island-jail for almost a century. But now, with its 400 acres of relatively undeveloped, uncontaminated land, public opinion has reached a consensus that the island would be better zoned as recreational open space for the ever-densifying Bronx and Queens neighborhoods nearby as well as prime real estate to be sold to the city’s growing research and educational institutions.

Our response to the Biennale’s theme “The Communal City, The Learning City” is a radical vision for the five-mile stretch of river between Randall’s Island to the west and Whitestone Bridge to the east, wherein the city begins a slow process of expansion into the river through new construction methods applied at the convergence of current social and economic forces:

1) It anticipates a growing need for slow infrastructure—roads and facilities aimed at creating safe outdoor recreational space specifically for pedestrians and cyclists—while providing a solution to the great transportational divide separating these two boroughs.

2) It sets in motion a massive undertaking to treat the last major source of pollution plaguing the river, with sewer overflow from all 139 C.S.O.’s being redirected to water treatment pipelines before flowing into the river.

3) It recovers a valuable piece of land much needed for future populations as the outer boroughs continue to densify, and at the same time affords opportunities for architectural innovation in the area of correctional facilities.

It is, we believe, a logical next step in the city’s development, and may be the key to correcting New York’s relationship with this formerly mistreated body of water.